Saab kicked off as a company making planes back in 1937. They called it Svenska Aeroplan AB, based in Trollhättan, Sweden, building fighter jets for the military before World War II hit. When the war ended, planes weren’t in high demand anymore, so Saab switched gears in 1945. Cars became their new focus, and they used their sky-high skills to whip up something wild.

Out came the Saab 92 in 1949—a funky little ride shaped like an airplane wing, super slippery with a drag coefficient of just 0.30. That’s slicker than some of today’s fancy hypercars! Painted dark green from leftover aircraft stock, this lightweight beast showed Saab could take flight on the road too.

Saab’s aviation roots ran deep, not just for show. They built cars thinking about airflow, safety, and saving gas—stuff straight out of jet design. That 92 had a unique two-cylinder, two-stroke engine mounted sideways, pumping out a modest 25bhp, but it sipped fuel like a champion. Right from the start, Saab didn’t care about being popular; they made rides for people who loved smart ideas over boring sameness.

Table of Contents

Cool Stuff Saab Cooked Up

Innovation defined Saab. Take the Saab 99 that rolled out in 1968—it brought front-wheel drive to bigger cars and tossed in goodies like headlamp wipers and heated seats. Those weren’t common until way later! Looking at top Saab cars, the 99 stands out for kicking off this trend of blending safety with style.

Then, in 1978, the Saab 99 Turbo dropped, one of the first affordable cars with a turbo attached. Not just for show, it mixed real power with everyday usefulness, pushing the whole car world toward turbo love.

Next up, the Saab 900 strutted in, also in 1978, and stole the show. Built off the 99’s foundation, it stretched into a slick hatchback, turbo optional, turning heads left and right. The key, stuck between the front seats by the handbrake, showed pure Saab weirdness, and fans loved it. Later, the 900 Convertible popped into the U.S., snagging folks who wanted odd over ordinary. Then came the Saab 9000 in 1984, going big for fancy buyers with tons of space, turbo kick, and that hatchback vibe—taking on BMW and Mercedes but still feeling like Saab.

Safety got Saab’s full focus too. They added side-impact bars, bumpers that fixed themselves, and tough crash-ready frames—overdoing it so much that profit took a hit.

The Saab 96, a rally monster with Erik Carlsson driving, snagged wins at the RAC and Monte Carlo races, proving tiny, weird cars could rule. These weren’t just extras; they screamed Saab’s “we do it our way” attitude.

Fans Who’d Die For It

Saab never moved massive units—think 24,000 9-3s a year in the U.S. during the mid-2000s, while BMW’s 3-Series blew past 100,000. Still, its fans were total freaks for it. Architects, brainy professors, and even Saab plane workers couldn’t get enough, preaching its gospel on random forums or Vermont backroads. It felt like Tesla nuts today, but quieter—no big social media buzz. They adored Saab because it was strange, not despite it.

That 9000 Turbo rolled smooth with power and space, while the 9-3 Turbo Convertible mixed daily driving with sneaky speed. Owners dug how these cars felt smart yet useful, offering pure Saab magic. These were not for the masses, and that made them special. Even when General Motors messed with its soul, fans held tight, crying over the fall but cheering the glory days.

GM Messed It Up Big Time

Things got tricky when General Motors nabbed 50% of Saab in 1989, and then all of it by 2000. GM wanted cash flow, but Saab rarely made money, and its bosses just shrugged. They kept pouring love into custom parts—the 9-3’s fancy rear suspension, the 9000’s safety overload—stuff GM’s penny-pinchers hated. Losses piled up—$848 million in 1990, like $9,200 per car sold. GM bigwigs, like Bob Lutz, lost their minds over Saab’s chill vibe.

GM tried slapping Saab badges on other rides—the 9-2X, a Subaru Impreza redo, and the 9-7X, a Chevrolet Trailblazer knockoff—to boost sales on the cheap. It flopped hard. True fans rejected the fakes, and U.S. buyers—the key to Saab surviving—didn’t bite. The 9-2X aimed at young drivers, and the 9-7X chased SUV hype, but neither felt like Saab. The 9-3 fought BMW and Audi but lacked their shine or big dealer support. By 2010, with the 2008 money crash hitting hard, GM ditched Saab, and it tanked in 2011.

Why America Didn’t Get It

Saab’s U.S. flop shows its guts—and its slip-ups. Too quirky to go big, it stayed stuck in a nerdy corner. Volvo sold safety to everyone; Saab’s brainy weirdness felt exclusive. Overbuilt cars cost too much, pricing out regular folks, and GM’s dumb moves finished it off. Those 9-2X and 9-7X disasters lost old fans and gained nothing, while German brands ruled sales.

But that flop doesn’t kill Saab’s shine. It proves they were too bold—or too dreamy—to bend. Toyota and Hyundai flipped their game for America; Saab said, “No, we’re us.” That’s why it’s awesome.

Still Kicking Somehow

Saab’s mark sticks around after its 2011 end. Turbos everywhere owe a nod to the 99 Turbo. Safety bars and more helped set industry rules. Volvo and Polestar keep Sweden’s car game alive, but Saab’s mix of plane vibes, rally grit, and useful oddness stands alone.

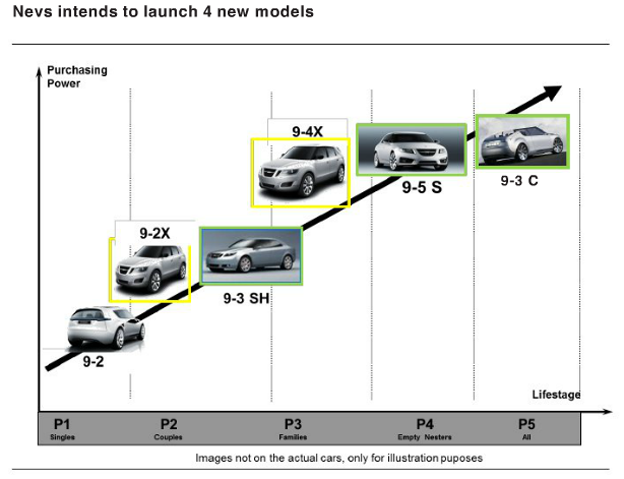

Revival tries—like Spyker or National Electric Vehicle Sweden—crashed due to cash woes and fights with Saab AB over the name. The car story’s done, but its heartbeats are still in old rides, and fans are still fixing up. A new Saab could’ve rocked as some sketches suggest, but what it did against the odds is the real deal.

Wrapping It Up: Greatness Isn’t Cash

Saab didn’t win by selling tons or dodging the corporate shredder. It won by being a total rebel. From the slippery 92 to the turbo 900, rally trophies to safety wins, Saab lived for new ideas, not copycat junk. Its diehards, unfazed by GM’s screwups or U.S. shrugs, prove it sparked love few brands touch.

Cars today can feel so dull, but Saab stood out—messed up, broke, and stuck in your head. That 2011 crash wasn’t about weak dreams; it was Saab refusing to sell out. That’s why it’s one of the greatest—not for profits, but for guts.